That Little Girl Who Resembles You Play

Date: Saturday, August 14, 1993

AlAyam NewsPaper Issue Number: 1623

Title: "That Little Girl Who Resembles You" A Bold Invocation of Literary Theater

By: Youssef Al-Hamdani

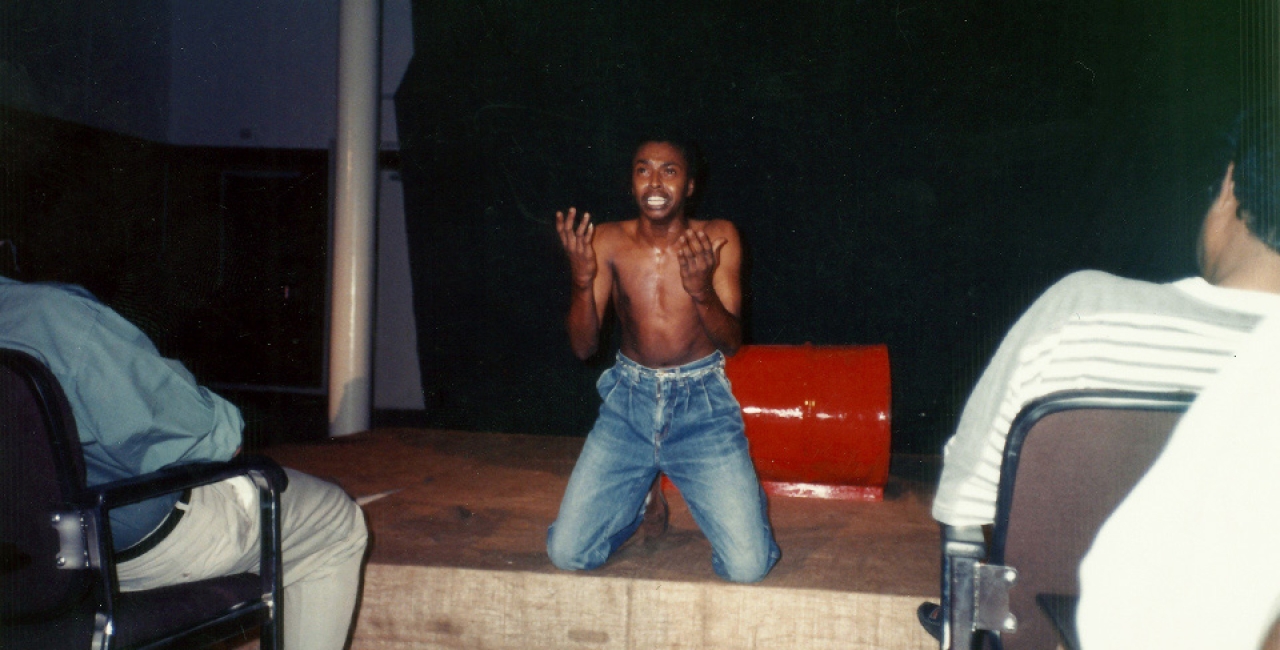

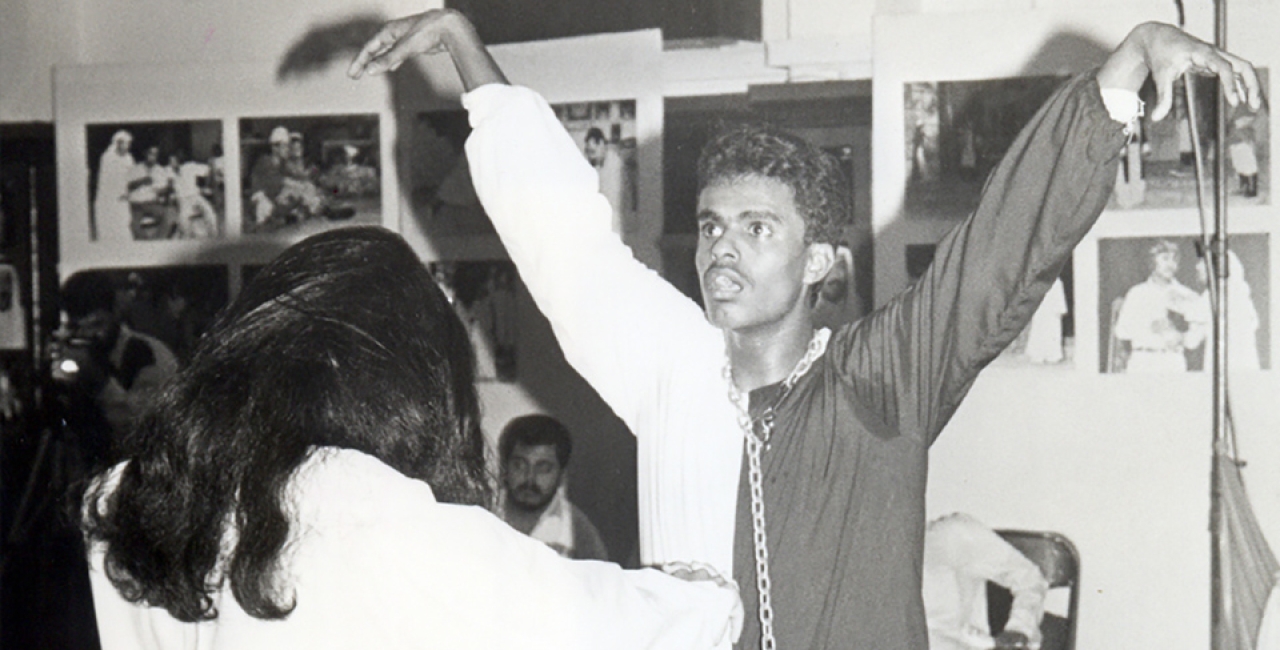

As part of the activities of the First Festival for Amateur Youth organized by the Sawari Theater, the young director Khalid Al-Ruwaie presented on the second day the play "That Little Girl Who Resembles You," which he himself composed and prepared. The play draws inspiration from various literary works such as "The Armor" by Qasim Haddad and Amin Saleh, "That Little Girl Who Resembles You" by Fareed Ramadan, and "The Flood" by the Lebanese writer Ghada Al-Samman.

This experiment included a group of amateur youth and children, some of whom had prior acting experience while others were performing for the first time. Nevertheless, we saw them in this performance exhibiting relatively equal levels of performance.

Initially, I was concerned about Khalid Al-Ruwaie, being a poet, might "lecture" his theatrical presentation, causing us to only interact with the words and nothing else. However, what happened—in my opinion—was quite the opposite. We were presented with a pure theatrical performance in an interactive atmosphere that demanded nothing but theater, in its movement, expressiveness, visual appeal, and intimacy. It was a bold step undoubtedly credited to the young director Khalid Al-Ruwaie. I believe such an approach has not been undertaken by any other director before, except for the experience of the critic Ibrahim Ghuloom in his play "I Saw What Will Happen," which, in my opinion, when it was directed on stage, was more of a rhetorical discourse rather than a theatrical one. It's indeed challenging to adapt literature—be it a story, poem, or novel—into theater. While some directors, like Abdullah Al-Saadawi in the play "Scorial," have incorporated literature into theater, they haven't delved deeply into literature itself and transformed it into a theatrical language, at least in terms of execution.

The performance relies on two fundamental themes articulated by the child character: In this world fraught with disappointment and horror, what remains for us? The scenes: Waiting, the only action that escapes everyone's control. Therefore, horror and disappointment, and waiting, are the main themes. The director registers his protest against this world when the witnessing dead character says: "For this reason, we must shape the meaning of the story and start from here." Or in his difficult question at the end of the show: "How can we sleep naked and not see our bodies heading towards a girl emerging from the grave?" These are cries against the horror and brutality that pervade this world.

Now, I'm not intending to criticize his choice of this text over others, although it's a very important issue that requires contemplation and patience. However, time will surely define the issue of this literary selectivity in the future. The actual protest begins when the director, Khalid Al-Ruwaie, ignites his torch among the torches scattered in the outdoor square and burns the effigy of evil, which symbolizes death and isolation, in the center of the square, leading them with his angry screams and guiding them from the exterior graveyard, blindfolded, wooden-bodied, shackled, towards the inner graveyard (the theater), where spectators' seats become part of the graveyard. In this graveyard, where the audience arises from their graves, where the dead witness their misery and embody it, the presence of the graveyard is undeniable. The witness arises, but perhaps its presence would be stronger if this graveyard traversed the audience's seats, even if this graveyard moves around the spectators and surprises them with screams of protest or questions.

The performance has three levels:

- The first level: The graveyard in the hall and the witnessing is alive.

- The second level: Characters interchange their roles from the stage to the graveyard in the hall.

- The third level: Characters remain fixed on the stage with their performances and movements.

I believe that the distinctive feature of this performance lies in the director's skillful creation of his world, engaging with it, condemning it, and exposing it. It's not an easy matter to accommodate all these characters, requirements, and backgrounds in this confined space. I think it's an impressive directorial and technical capability deserving of appreciation. We truly need wide-ranging vision to interact with this terrifying world. It's a stage brimming with action. At the same time, we see here static and dynamic images, some dancing, some speaking, some silently expressing, all of which we support with musical effects, lighting, and screams emanating from here and there. It's a spot of beauty that somewhat transcends the prevailing traditional reception and the conventional aesthetic design in our theater. I believe that the responsibility of tackling another performance for the director will undoubtedly be significant. But as long as this youthful energy continues to emerge from the womb of madness and plays on its strings, there's great confidence in it. Hats off to the entire team of the show, represented by all its artists without exception: Shaima Sabt, Mohammed Haddad, Ibrahim Al-Mansi, Kaltham Al-Shatti, Hussain Al-Halabi, Wafa Mohammed, Nader Abdul Aal, Rita Al-Halal, Ghazwa Ibrahim, Shatha Sabt, Ali Issa, Abdullah Al-Khatim, Mohammed Saeed, Munir Saif, Mohammed Ridwan