His mind never rests, nor does a cell fail to develop in his head or imagination unless he engages in a theatrical experiment, Every Ramadan, he harnesses his energy to ignite the energy of the members of the Sawari Theater who gather with him every night to engage in his experiment.

He is not much concerned with the institutions of negative polarization that overflow greedily onto the surface of events like Ramadan, with its contrasting effective creative data.

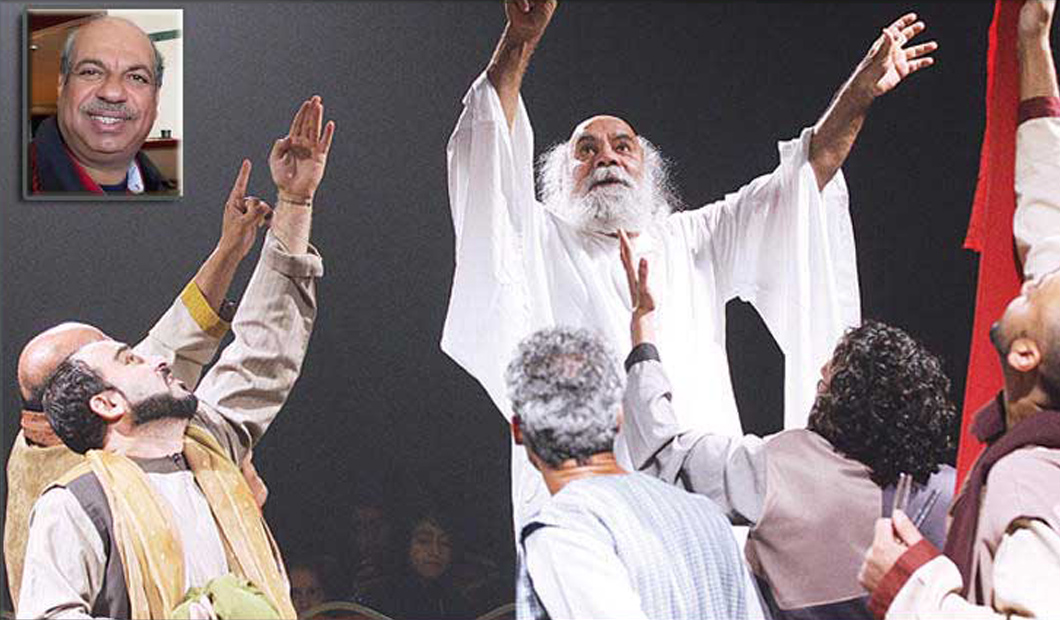

He is the problematic artist and director Abdullah Saadawi, who invoked his deep research experience in Ramadan in the drama of Qurban or the tragedy of Hallaj, Abu al-Hussein ibn Mansur, Hallaj al-Asrar, Abu Abdullah al-Zahid, Al-Muqit al-Mughith, Al-Muhair, Al-Mumayyaz, Al-Musta'im.

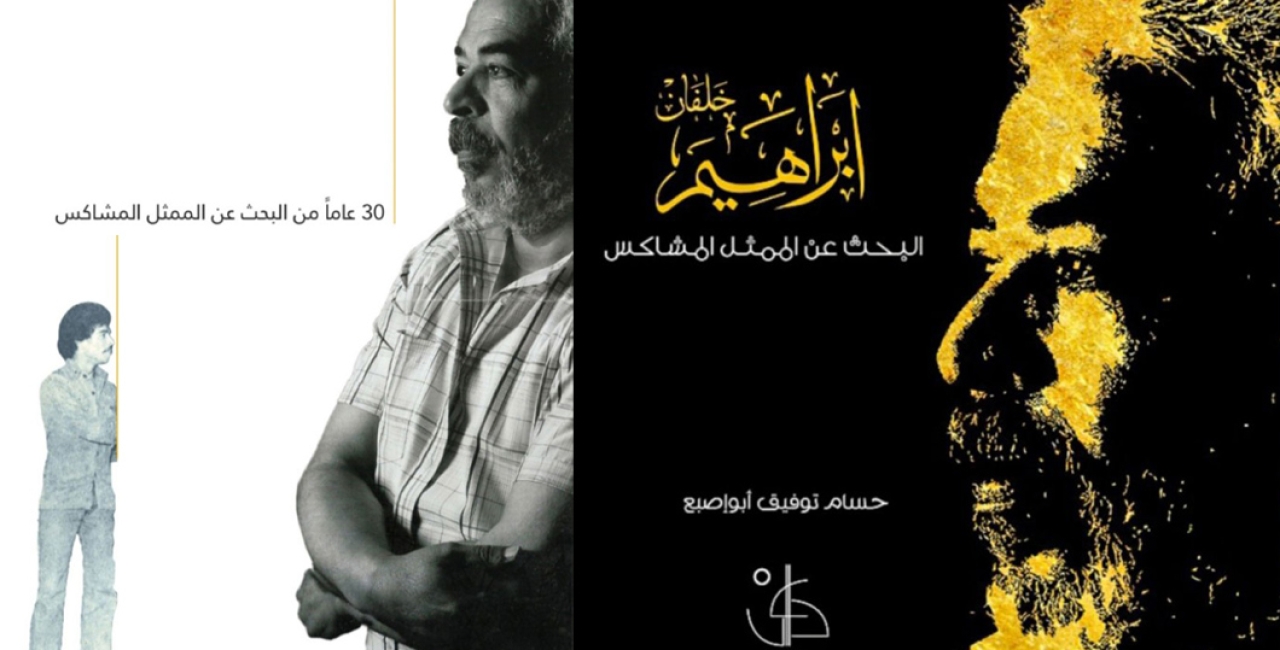

Saadawi read Hallaj by the Egyptian poet and writer Salah Abdel Sabour and was passionately drawn to Sufism, so he began to search for it and about it in the depths and layers of Sufism in various religions, sects, beliefs, and genres, with the sheikhs, old poles, and modernists, among those who believe in it and those who oppose it. He read Hallaj in Persia, his homeland, and in India where he immersed himself in wisdom and magic, and in Mecca where he withdrew into asceticism, and in Basra and Baghdad where the poles, sheikhs, scholars of religion, thought, and Sufism, and where he met his death there unjustly and oppressively.

Saadawi, of course, did not neglect to read and immerse himself in the book of Hallaj (Al-Tawasin), the only book that, as it is said, was found, and his attempt to read through many references to analyze and dismantle its symbols, letters, and puzzles, in the sense of how his teachers, students, or followers read it, and perhaps the most important references that captured the spirit of Saadawi was the book (Futuh al-Ghaib) by the pole of poles Sheikh Abdul Qadir al-Jilani, that sheikh who, as it is said, is better than Husayn ibn Mansur al-Hallaj.

During the month of Ramadan and before it and after it, Saadawi prepares and reprepares his directing plan or vision for the performance, including his perceptions, drawings, or initial sketches and the references of the show and pictures and drawings collected from some books that document the life and tragedy of Hallaj. He puts this vision plan in a file specific to Hallaj, which Saadawi presents to anyone chosen to work with him to accurately understand his vision for this show. He also provides some of the references contained in it or clippings to some of his friends to read and then discuss with him. AlSaadawi specified in Ramadan of that year (February 1995) the actors who would be assigned these roles, namely Khalid al-Ruwai'i who played the role of Hallaj, and distributed the rest of the roles to some who trained with him during the nights of Ramadan that year, such as Hussein al-Halabi, Mohammed Haddad, Salman al-Araibi, Shaima Sabbat, Yasser al-Qarmuzi, Mohammed Mubarak, Walid Hussein, and a large number of choir members, assistants, and technicians, including the scenic artist Mohammed Radwan.

Saadawi does not suffice with training his team at the theater headquarters, but he tries, starting from the fourth day of Ramadan, to adapt them to other external environments, and in the theater library, Saadawi conducts his rehearsals with calm and intense concentration, which makes him devoted to training the actor on a word, tone, gesture, movement, or expression for sometimes more than an hour, in order to keep the members of the theater engaged in his experiment, he tries to assign them some tasks. He wants Ramadan of 1995 to be like Ramadan of the previous year, 1994, in which he completed the experiment (Al-Kamama) while most of the theater workers were occupied with other artistic tasks, and some bet on the impossibility of achieving a theatrical experiment in the month of Ramadan.

I miss you a lot, my friend... This Ramadan needs your creative spirit."